August 30, 2013

Rupert Japanese internment camp

http://www.minicassia.com/news/local/article_f6740b5c-10ce-11e3-881e-001a4bcf6878.html

Rupert Japanese internment camp

Posted: Thursday, August 29, 2013 11:18 am

Rupert Japanese internment camp

In an effort to appease the public, photos taken at Japanese internment camps showed happy detainees as, in this photo of a children’s performance. An exhibit of such photos will be presented at the Minidoka County Museum in 2015. Prior to the government detaining Japanese-Americans at the Minidoka “Hunt” Camp, officials set up a temporary camp in Rupert on North F Street in 1942.

By Lisa Dayley | 0 comments

RUPERT – At one time the government set up a temporary Japanese Internment Camp on South F Street.

Minidoka Museum official Ginger Cooper recently came across the information and announced the discovery on Friday. According to Cooper, the government created the camp in 1942, just months following the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. At the camp, Japanese-Americans, forced from their homes along the west coast, stayed for about a month until contractors finished the Minidoka (Hunt) Camp in Jerome.

Nobody knew anything about this camp until Oregon researcher Morgan Young came across a one paragraph newspaper report from the “Minidoka County News” from 1942 placed online, Cooper said.

After reading the newspaper report, Young assumed that the main Minidoka Camp had been built in Rupert. Many people – and especially Japanese-American descendents of those camps – believe the government built the main camp in Minidoka County. The government transported the internees through Minidoka City via train before taking them to Jerome.

“We get people calling and stopping here looking for the Minidoka Camp. We always have a good supply of maps here to help them,” Cooper said.

Young contacted Cooper about the camp, and, after doing some research, the women realized the report Young came across was that of a temporary camp on F Street.

“None of us knew that it was here,” Cooper said.

The government housed Japanese there in a makeshift tent city for about 30 days prior to moving them to Minidoka Camp.

While there are no pictures available of the temporary camp, researchers have gathered pictures of Japanese internees from throughout the west that will be part of an exhibit to be displayed in Idaho from January to May 2015. For part of that time, it will be kept at the Minidoka County Museum. Officials also plan to display the photos in Jerome and Twin Falls where there were also internment camps.

Researchers have spent years tracking down pictures and identifying those Japanese-Americans photographed. A National Geographic photographer shot the photos that show pictures of smiling Japanese – living behind barbed wire.

“The pictures were all staged. It’s so the people who were buying National Geographic wouldn’t feel bad about what we did,” Cooper said.

The photographer took pictures of Japanese internees working in the fields, folding American flags, swimming and going to school.

“He literally took millions of pictures,” Cooper said.

The museum is open from 1 to 5 p.m., Tuesday through Saturday and is located at 99 East Baseline Road. In October it will be open from 1 to 5 p.m., Monday through Saturday. Admittance is free. For more information call the museum call 436-0336.

August 2, 2013

Researchers uncover little-known Idaho internment camp

http://seattletimes.com/html/localnews/2021488263_internmentcampxml.html

Originally published Saturday, July 27, 2013 at 2:24 PM

Researchers uncover little-known Idaho internment camp

A team of researchers from the University of Idaho wants to make sure the Kooskia Internment Camp isn’t forgotten to history.

The Associated Press

Deep in the mountains of northern Idaho, miles from the nearest town, lays evidence of a little-known portion of a shameful chapter of American history.

There are no buildings, signs or markers to indicate what happened at the site 70 years ago, but researchers sifting through the dirt have found broken porcelain, old medicine bottles and lost artwork identifying the location of the first internment camp where the U.S. government used people of Japanese ancestry as a workforce during World War II.

Today, a team of researchers from the University of Idaho wants to make sure the Kooskia Internment Camp isn’t forgotten to history.

“We want people to know what happened, and make sure we don’t repeat the past,” said anthropology professor Stacey Camp, who is leading the research.

It’s an important mission, said Charlene Mano-Shen of the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience in Seattle.

Mano-Shen said her grandfather was forced into a camp near Missoula, Mont., during World War II, and some of the nation’s responses to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, evoked memories of the Japanese internments. Muslims, she said Thursday, “have been put on FBI lists and detained in the same way my grandfather was.”

After the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor plunged the nation into the Second World War, about 120,000 people of Japanese heritage who lived on the West Coast were sent to internment camps. Nearly two-thirds were American citizens, and many were children. In many cases, people lost everything they had worked for in the U.S. and were sent to prison camps in remote locations with harsh climates.

Research such as the archaeological work under way at Kooskia (KOO’-ski) is vital to remembering what happened, said Janis Wong, director of communications for the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

People need to be able “to physically see and visit the actual camp locations,” Wong said.

Giant sites where thousands of people were held — such as Manzanar in California, Heart Mountain in Wyoming and Minidoka in Idaho — are well-known. But Camp said even many local residents knew little about the tiny Kooskia camp, which operated from 1943 to the end of the war and held more than 250 detainees about 30 miles east of its namesake small town, and about 150 miles southeast of Spokane.

The camp was the first place where the government used detainees as a labor crew, putting them into service doing road work on U.S. Highway 12, through the area’s rugged mountains.

“They built that highway,” Camp said of the road that links Lewiston, Idaho, and Missoula.

Men from other camps volunteered to come to Kooskia because they wanted to stay busy and make a little money by working on the highway, Camp said. As a result, the population was all male, and mostly made up of more recent immigrants from Japan who were not U.S. citizens, she said.

Workers could earn about $50 to $60 a month for their labor, said Priscilla Wegars of Moscow, Idaho, who has written books about the Kooskia camp.

Kooskia was one of several camps operated by the Immigration and Naturalization Service that also received people of Japanese ancestry rounded up from Latin American countries, mostly Peru, Camp said. But it was so small and so remote that it never achieved the notoriety of the massive camps that held about 10,000 people each.

“I’m aware of it, but I don’t know that much about it,” said Frank Kitamoto, president of the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Memorial Committee, which works to maintain awareness of the camps.

After the war the camp was dismantled and largely forgotten. Using money from a series of grants, Camp in 2010 started the first archaeological work at the site. Some artifacts, such as broken china and buttons, were scattered on top of the ground, she said.

“To find stuff on the surface that has not been looted is rare,” she said.

Camp figures her work at the site could last another decade. Her team wants to create an accurate picture of the life of a detainee. She also wants to put signs up to show people where the internment camp was located.

Artifacts found so far include Japanese porcelain trinkets, dental tools and gambling pieces, she said. They have also found works of art created by internees.

“While it was a horrible experience, the people who lived in these camps resisted in interesting ways,” she said. “People in the camps figured out creative ways to get through this period of time.”

“They tried to make this place home,” she said.

August 1, 2013

Johnny’s story

The words below are Johnny Valdez’s story. He shared his powerful story with all of the attendees at the 2013 Minidoka Pilgrimage.

June 22, 2013

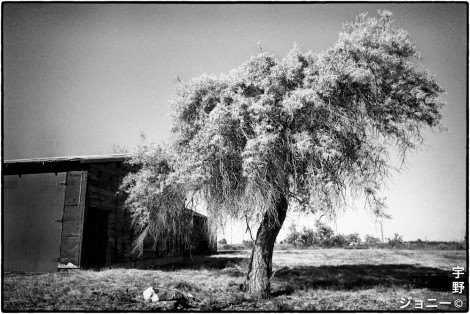

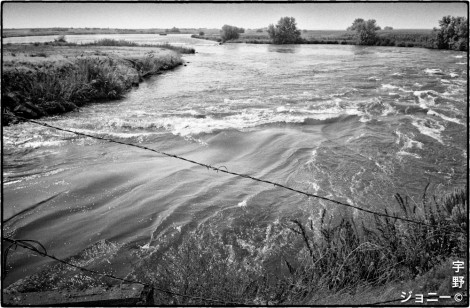

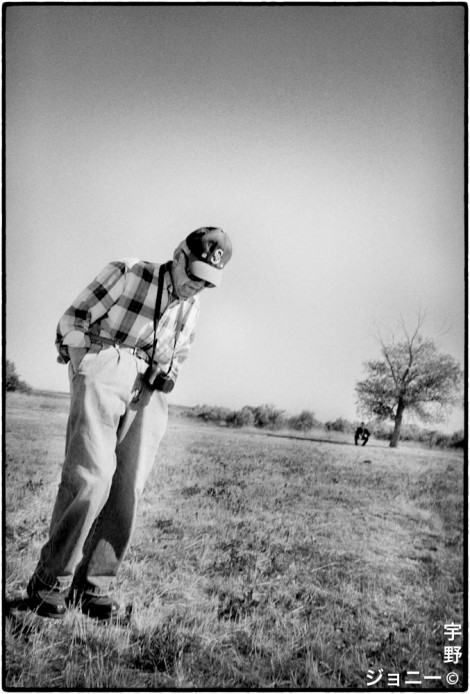

– Twin Falls, ID – My name is Johnny Valdez. I am a Seattle based photographer, and I currently have a running photo exhibition entitled, “My Minidoka”. I am the son of a Sansei mother, and a Latino American Father, Grandson of two Nisei who were once incarcerated here at Minidoka along with their families. As everyone has a story, this one is mine, and it is an extension of theirs’ as well.

I photograph what I love, and what draws me in. My Grandparents are no longer living, so it is with immense compassion and sensitivity that I go about photographing our surviving Nisei. This is because when I take that picture of what I am seeing, I am essential taking a picture of my own Grandparents, and that is what I love.

In camp, my Grandmother’s name was Porky Noritake. She went to Hunt High School, and was in a band called the Minidoka Matinee. She sang songs on the radio like “Shina No Yoru” and “Don’t Fence Me In”. Her older brother Yosh, was in the 442nd’s 100th Battalion, and was killed in action in Bruyeres, France during the rescue of the lost Texas Battalion.

My Grandfather’s name was Johnny Uno. He was four years older than Porky and graduated from Hunt High School in 1943. He went into the Army, and after training at Camp Shelby was assigned to the 442nd. He served in Italy, Switzerland, and Germany. After the war he went to school on the G.I. Bill, and later became a podiatrist.

My work entitled “My Minidoka” is dedicated to my grandparents, Johnny and Porky Uno.

“My Minidoka” is a personal project and an expression that I have been incubating for several years. It is my take on the Minidoka experience through my eyes and its impact on my own life. It comes from my heart. And it is an ongoing lifelong study of ideas and emotion that continues to evolve and manifest, as I often come to revisit it. It has had a profound effect on who I am as a person.

I was not there at Minidoka during the Second World War, but I have a deep emotional connection to it, as it has greatly affected my life. Like many defining moments in the lives of people, this for me was an impacting awakening of sorrow and tragedy. I first learned of the wrongful injustices and incarceration of a people, my people, when I was 8 years old. It was the 28th of May, 1990 – Memorial Day. This day would forever change the course of my life, and this would be the day when I would come to know Minidoka.

My father woke me up in tears repeating my name, “Johnny, Johnny, Johnny…” Soon after, he told me that there had been a car accident. “Grandpa died,” he said, “Auntie Mickey died and Uncle Toshi too,” he continued. I was breathless and in unimagined disbelief. It was awful. In tears I asked, “What about Grandma?” “Grandma is alright,” he said. And although I was experiencing a pain that I had never felt before, I was greatly relieved that I still had my grandmother.

The four of them were on their return journey home to Seattle from a pilgrimage to Minidoka when this fateful tragedy occurred. My father further explained to me the circumstances, significance and purpose of my grandparents’ and their siblings’ journey to this place in Idaho.

I was extremely close to my grandparents, and learning about mortality and impermanence in this traumatic way, I remember thinking that I never wanted to leave my grandmother’s side. During those days I even used to sleep on the floor next to her bed. I found myself extremely curious and inquisitive about these unique lives and the history of my grandparents, and my grandmother was my key to the past.

For years she and I shared in great conversations, and I was full of questions. She spoke of the shame, struggle and trauma of her people that once was, and which now transcends into great pride. Our people lost everything. We have shed our own blood to prove our loyalty and allegiance to the only country that we have ever called home.

Now as I take on this journey with this project, I navigate my way through the past. This work is a homage to my people. It is with immense compassion that I capture these moments, expressions and feelings. My images tend to carry more of a heavier tone and feeling, but in them there is love, and that comes from my heart. This is why I take these pictures. In the words of my Grandmother, “Shoganai! Gaman!”